This is the first in a two post commentary by guest blogger Jeremy Speres of Floor Swart on the Supreme Court of Appeal decision in BMW v Grandmark which was delivered last week. This post deals deals with the alleged design infringement by BMW. The second post provides further commentary, addressing whether this decision does actually spell the end of spare part protection under design law in South Africa, as well as dealing with trade mark aspects of the decision.

|

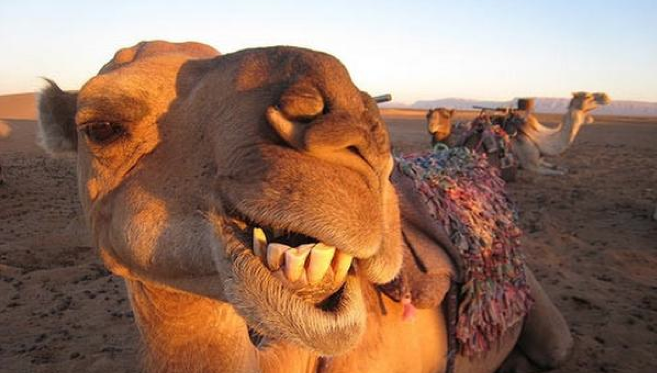

| S14(6)-are those teeth sharp ? |

"Two

members of the statutory committee appointed to review the predecessor to the

current Designs Act once decried the current Act as follows: “the Act is rather

like a camel…in the humorous sense of a camel being a horse

designed by a committee” (as quoted in Burrells South African Patent and Design

Law, citing Prof.

Coenraad Visser

in turn).

The parties

in the long-running BMW v Grandmark

dispute are all too familiar with the camel-esque nature of parts of the

Designs Act. Prof. Roshana Kelbrick

previously summarised the facts and the findings of the High Court in a

sterling piece on this blog here. After BMW appealed the matter to the Supreme

Court of Appeal, it was the turn of the Bloemfontein court to attempt to smooth

the camel’s back.

Alas, for

those readers who had hoped for some clarity as to the scope of section 14(6)

of the Designs Act, the appeal court expressly declined to consider it (see

para 7). Despite this, the appeal court

did however concur with the High Court in a manner that will make it very

difficult for spare parts to be protected through the Designs Act in future. Section 14(6) can be read here.

Prior

to the High Court decision, the general thinking was that section 14(6)

prevents the protection of spare parts as registered functional designs, but

that they could possibly be protected as aesthetic designs (provided the Act’s other

requirements are met) as a result of the legislature not expressly including

aesthetic designs within the ambit of the section 14(6) exclusion. However, as Prof. Wim

Alberts and Sara-Jane Pluke

(the latter successfully represented Grandmark before both courts) have pointed

out in an erudite piece in Without

Prejudice (September 2012), the High Court effectively adopted an approach

that extended the section 14(6) exclusion to aesthetic designs as well. This was a result of the court’s finding that spare

parts are, by their nature, wholly functional (their sole purpose being to

replace other parts), and are therefore not registrable as aesthetic designs. The appeal court concurred (see para 13).

On

appeal BMW raised the argument that its spare parts are not wholly functional but

incorporate elements that “appeal to and are judged solely by the eye”,

entitling them to registration as aesthetic designs. In this regard, BMW argued that because the

designs of its vehicles as wholes qualify for aesthetic design protection, it

follows that their constituent components must too. The court dealt with this swiftly, stating

that the component designs must be judged on their individual qualities,

independently of the vehicle as a whole.

They are not selected because they appeal to the eye, but solely for the

function they perform – to restore the vehicle to its original form (see paras

12 – 13).

|

| Cheetah beater |

To counter

such reasoning, BMW submitted that an owner of one of its vehicles may

conceivably choose to replace an original component with a component of a

different design in order to modify the appearance of the vehicle, indicating

that components do in fact have aesthetic qualities. The appeal court however reversed that

submission and found that it had to consider BMW’s components as covered by

their registered designs and not the modified components of others instead. In the words of the court, “Perhaps there are eccentric motorists to

whom it might appeal to fit a BMW fender, for example, to a vehicle of a different

kind – though it is difficult to imagine one – but the designs are not to be

judged by their appeal to eccentricity.”

It is at this point in the judgement that one gets the distinct

impression that we won’t be seeing Nugent JA (who wrote the unanimous

judgement) driving around with a giant tail wing anytime soon…

Accordingly,

the appeal court agreed with the High Court and held that BMW’s aesthetic

designs were purely functional and fell to be revoked."