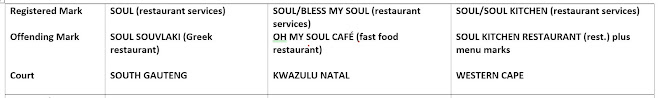

In each of the three divisions, the primary infringement claim was rejected. Where a counter claim was raised against the descriptive nature of SOUL (as in e.g. soul food), the argument was found to have some merit but nonetheless rejected, and there was even a finding that the mark SOUL was well known for the purposes of dilution (which was then summarily dismissed).

It should be appreciated that all three cases were brought on trade mark infringement grounds alone, and did not include passing off and unlawful competition, yet in all three cases, the court erred in the basic application of the infringement test by comparing the use made by Chicken Licken with the offending use i.e. a passing off type test, in finding that a likelihood of confusion did not exist between the marks.

The high oil mark, so to speak, is the final paragraph in the Kwazulu Natal case where the judge introduced the concept of “ubuntism” (the spirit of humanity) by suggesting that Chicken Licken, should, in the national interest, encourage rather than restrain use of SOUL, and that small businesses should be protected from trade mark infringement claims of larger organisations!

Whether or not you agree that any single proprietor should have exclusivity to SOUL for restaurant services or food, the reality is that, absent a successful or part cancellation claim, Chicken Licken have registered trade marks for the full gamut of “restaurant services” (which includes Greek restaurant services, café services and kitchen services) that attracts certain rights. These rights are to be able to stop identical and confusingly similar marks. On a basic application of the infringement tests SOUL SOUVLAKI, OH MY SOUL and SOUL KITCHEN (including logo marks) are simply, dead meat and should be capable of being stopped.

Why

then were the judges so reluctant to grant the interdicts. Was it because Chicken

Licken was too aggressive and corporate against likeable cottage style eateries?

Was it because exclusivity in SOUL just feels wrong? Was it because the infringement

test as constructed and set out in Plascon Evans (SA leading case) and others, easily leads to conflation and confusion,

especially for judges who do not adjudicate trade mark cases on a consistent basis.

One gets the sense that the answer to all of these questions may have been “yes” because in some places, the findings are difficult to reconcile and in other places just downright wrong. But, in my humble opinion, the answer to the final question is the most emphatic “yes!”. If one takes the time, in the pleadings and the judgement, to break down the Plascon Evans test into its individual components and apply them step-by-step (an approach long advocated by this blog - see here), the chances of tossing the equivalent of a frozen chicken leg into super hot oil in a trade mark judgement, are reduced significantly.